“It is hard to over-value the powers of the clever tracker. To him the trail of each animal is not a mere series of similar footprints; it is an accurate account of the creature’s life, habit, changing whims, and emotions during the portion of life whose record is in view.” –Ernest Thompson Seton, Boy Scout Handbook, 1911

When following an animal’s footprints, try to track towards the sun if possible, as the shadows will make the impressions stand out more. The sun’s position in the sky during the early morning and late afternoon will particularly enhance the tracks.

Source

Books Of Interest:

The other day while hiking some muddy trails with my family, my son pointed to a set of tracks and asked me what animal had made them. “That’s easy,” I said, “those are the tracks of a whitetail deer.” “What about those?” he asked, pointing to another set of footprints. “Those are, um, hmmm, well, I’m not sure what they are,” I confessed. I realized I needed to brush up on my knowledge of animal tracks.

Learning how to track and identify the footprints of animals is an ancient and largely forgotten art — one that’s not only important for hunters, but also enhances any outdoorsman’s experience in the wild. It’s fascinating to know what creatures are sharing the woods with you, and trying to track them down by following their trail is a lot of fun. Learning how to read tracks allows you to pick up on the little dramas enacted by wildlife that usually go unnoticed by the human eye. It’s thus a skill that both deepens your understanding of nature and heightens your all-important powers of observation.

Becoming an expert tracker takes years of practice. To get you started, today we offer a primer on the basics of identifying the footprints of common animals. We’ve taken as our guides two master woodsmen of yore — Ernest Thompson Seton, one of the founders of the Boy Scouts, and Charles “Ohiyesa” Eastman, who was raised as a Sioux tribesman — as well as drawn on tips from Tom Brown Jr., one of the foremost modern trackers.

Let’s head into the woods and see what we can discover!

Where to Look for Tracks

“Never lose the chance of the first snow if you wish to become a trailer.” –Ernest Thompson Seton

Winter is primetime for animal tracking, as the prints are easy to find in the snow and can be followed for a long distance. However, as Seton explains:

“the first morning after a night’s snow fall is not so good as the second. Most creatures ‘lie up’ during the storm; the snow hides the tracks of those that do go forth; and some actually go into a ‘cold sleep’ for a day or two after a heavy downfall. But a calm, mild night following a storm is sure to offer abundant and ideal opportunity for beginning the study of the trail.”

The drawback of snow tracking is that in deep, soft snow you may find only the holes made by the animal’s feet and legs. Further accumulation and melting can also easily obscure the trail. And of course, some animals don’t come out at all during the winter because they are hibernating.

For these reasons, mud and fine, wet sand can be an even better medium, as they hold the shape of the footprint well. A mudbank stream is one of the best places to look for tracks, as it’s frequented by shore birds and waterfowl as well as animals like the raccoon and muskrat looking for food. After a rain, sand bars, ditches, and muddy gullies are also fruitful places to find the tracks of deer, possums, and other creatures. Looking over a dewy, open field in the morning can reveal the tracks creatures made in the night as well.

Whether in snow or dirt, a track is best and easiest to follow when it is freshest — before wind, rain, melting (in the case of snow), and debris have obscured the prints.

While it’s surely fun to track animals through the wilderness, it’s also enjoyable to try to find their footprints in your very own backyard (and around the trashcan!). So always be aware of your surroundings wherever you go, and you never know what you’ll see.

Learning the Tracks

In learning which tracks belong to which animals, it can help to know the basic classifications of common animal families. Simply by counting the number of toes in a footprint, you can figure out which family the creature belongs to, and from there work on narrowing down which species you’re looking at.

In this narrowing down process, it’s useful to know which animals are common to your area. As Seton explains, “In studying trails one must always keep probabilities in mind”:

“Sometimes one kind of track looks much like another; then the question is, ‘Which is the likeliest in this place.’If I saw a jaguar track in India, I should know it was made by a leopard. If I found a leopard in Colorado, I should be sure I had found the mark of a cougar or mountain lion. A wolf track on Broadway would doubtless be the doing of a very large dog, and a St. Bernard’s footmark in the Rockies, twenty miles from anywhere, would most likely turn out to be the happen-so imprint of a gray wolf’s foot. To be sure of the marks, then, one should know all the animals that belong to the neighborhood.”

Below you’ll find illustrations of the footprints of the track classifications for the most common families of animals; they break down not only what the tracks look like when the animal is walking (which is its typical gait), but also hopping/running (which it may do when chased by a predator, or doing some chasing of its own).

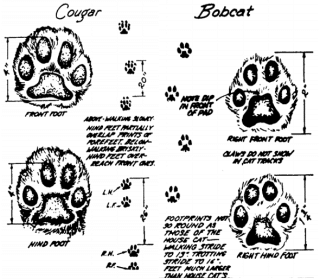

Cats

Cats leave rounded prints that show four soft, pliable, spread toes. The prints lack claws, since they’re retractable. A cat also walks in what’s called a “single register” — its hind legs exactly track its front legs, so that it appears to only be walking with two legs, rather than four. This aids in quiet, stealthy stalking.

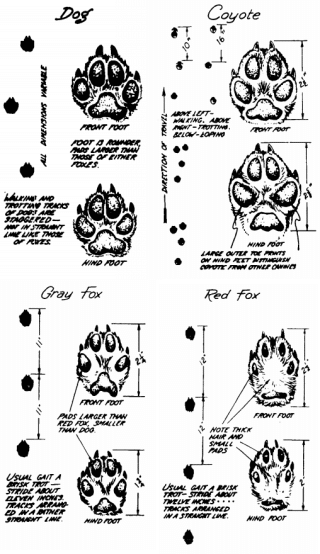

Canines

Canines have four toes like cats, but their feet are harder and their claws can be seen as they don’t retract. While the fox walks in a single register, dogs and coyotes walk in an indirect register — their hind legs land a little behind and to the side of the front print, leaving a messier track than that of a cat.

Weasels

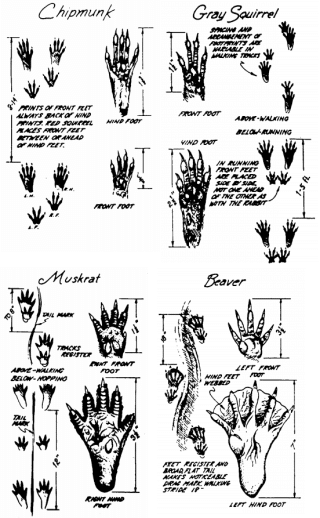

Members of the weasel family have five toes on both their front and hind feet, though all five don’t always show in the track.

Five-Fingered Outliers

While bears, possums, and beavers don’t belong to the weasel family, their tracks are similar in that they also have five toes in both back and front. However, they differ in the flat, human-like nature of their feet.

Rodents

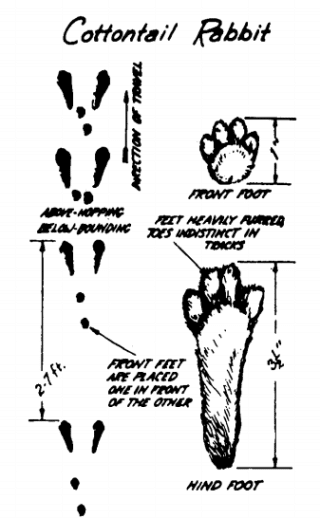

Hares & Rabbits

Rabbits have four toes on both their front and rear feet, and in almost all species the back feet leave tracks that are at least twice the size of the front.

Hoofed Animals

The tracks of hoofed animals are easy to recognize, and deer tracks are some of the most common to find in the woods. You can distinguish a doe from a buck, in that the female has sharper hoofs and a narrower foot than the male.

Tips for Following the Trail

“I will now ask you to enter the forest with me. First, scan the horizon and look deep into the blue vault above you, to adjust your nerves and the muscles of your eye, just as you do other muscles by stretching them. There is still another point. You have spread a blank upon the retina, and you have cleared the decks of your mind, your soul, for action.Now that you know what the tracks look like, how do you follow the trail once you’ve identified it?

It is a crisp winter morning, and upon the glistening fresh snow we see everywhere the story of the early hours — now clear and plain, now tangled and illegible — where every traveler has left his mark upon the clean, white surface for you to decipher.

The first question is: Who is he? The second: Where is he now? Around these two points you must proceed to construct your story.” –Charles Eastman (Ohiyesa), Indian Scout Talks, 1915

When following an animal’s footprints, try to track towards the sun if possible, as the shadows will make the impressions stand out more. The sun’s position in the sky during the early morning and late afternoon will particularly enhance the tracks.

As you follow an animal’s tracks, don’t just focus on the discrete sets of prints themselves, but continually take in the trail as a whole — which may in fact be easier than finding individual footprints. For example, by looking ahead, instead of having your nose to the ground, you may see a trail of bent grass through a field. Also look for other disturbances like cracked twigs, or pebbles and leaves that have been overturned to reveal their darker, wetter undersides. If you lose the trail, place a stick by the last set of prints you discovered and then walk around it in an ever widening spiral until you pick up the trail again.

Eastman lays out other considerations for your hunt:

“It is essential to estimate as closely as you can how much of a journey you will undertake if you determine to follow a particular trail. Many factors enter into this. When you come upon the trail, you must if possible ascertain when it was made. Examine the outline; if that is undisturbed, and the loose snow left on the surface has not yet settled, the track is very fresh, as even an inexperienced eye can tell…It will also be necessary to consider the time of year. It is of no use to follow a buck when he starts out on his travels in the autumn, and with the moose or elk it is the same.”

Conclusion: What the Trail Gives — The Secrets of the Woods

Animal tracks are the alphabet of the wild — an education in their language can help you read more of the nature all around you. As Seton concludes, knowing this language opens books of the woods and its inhabitants that would otherwise be closed to you:“There is yet another feature of trail study that gives it exceptional value — it is an account of the creature pursuing its ordinary life. If you succeeded in getting a glimpse of a fox or a hare in the woods, the chances are a hundred to one that it was aware of your presence first. They are much cleverer than we are at this sort of thing, and if they do not actually sight or sense us, they observe, and are warned by the action of some other creature that did sense us, and so cease their occupations to steal away or hide. But the snow story will tell of the life that the animal ordinarily leads — its method of searching for food, its kind of food, the help it gets from its friends, or sometimes from its rivals — and thus offers an insight into its home ways that is scarcely to be attained in any other way.The trailer has the key to a new storehouse of nature’s secrets, another of the Sybilline books is opened to his view; his fairy godmother has indeed conferred on him a wonderful gift in opening his eyes to the foot-writing of the trail. It is like giving sight to the blind man, like the rolling away of fogs from a mountain view, and the trailer comes closer than others to the heart of the woods.

Source

Books Of Interest:

No comments:

Post a Comment